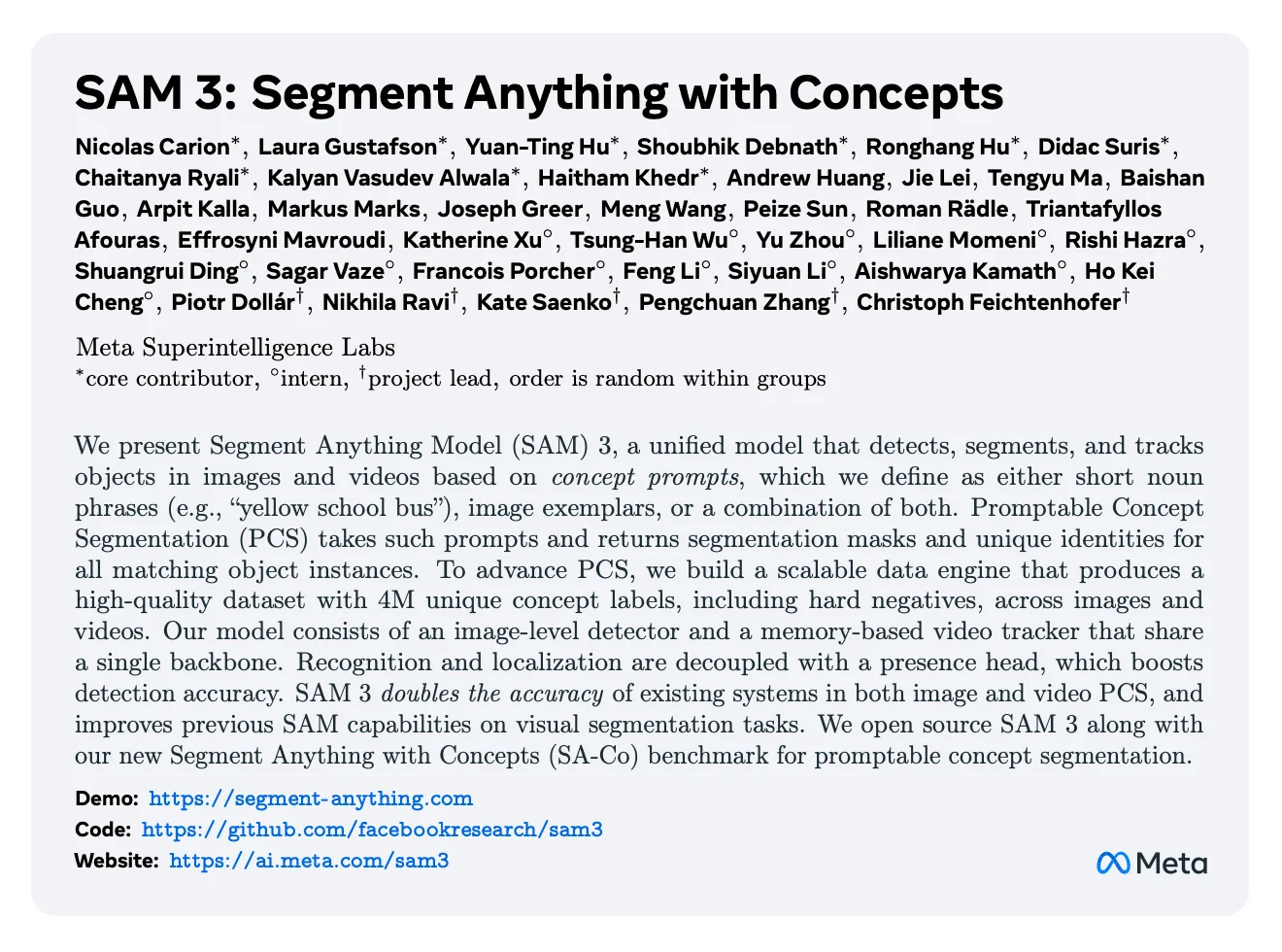

Meta Segment Anything Model 3 (SAM 3) is easy to describe in terms of capability: it takes a prompt—often a simple noun phrase, text prompt, or image exemplar—and returns segmentation masks for the objects that match. It also extends this idea to video by producing masklets—spatio-temporal masks that persist across video frames.

But the more interesting story is not the architecture diagram or a leaderboard row. It's the data system behind it.

Thankfully, Meta's habit of sharing as much as they can on the data treatment of their models, such as Llama 3.1 continues with SAM 3.

SAM 3's headline claim is that open vocabulary segmentation becomes meaningfully better when you stop treating "training data" as a fixed, one-off dataset—and instead treat it as a living pipeline that continually finds failure cases, generates labels, filters them, and repeats. In the paper, this pipeline is called the data engine, and it is at least as important as the model itself.

This article focuses on that data story end-to-end:

- How the training data was built (including the ontology that shapes what gets collected).

- How it was filtered and curated (especially the verification steps and hard negatives).

- How post-training and fine-tuning depend on data quality (not just "more steps").

- How evaluation is treated as data (benchmarks as distributions, not just scores).

Along the way, we'll keep returning to one practical question: what experiences did this system learn from, and how did the filtering and curation choices shape the behavior that shows up in benchmarks?

1) What SAM 3 Is Trying to Learn

The core task in the paper is Promptable Concept Segmentation (PCS). The input is a piece of media (image or video) and a short text prompt or visual prompt—typically a noun phrase like "a computer monitor" or "yellow school bus," or an image exemplar showing the target concept. The output is:

- A set of pixel accurate masks for every instance that matches the phrase, and

- An explicit "present / not present" decision (because many concept prompts are negatives).

Unlike SAM 1 and SAM 2, which segment single objects per prompt, SAM 3 introduces promptable concept segmentation that can find and segment every occurrence of a concept appearing anywhere in images and videos. This represents a fundamental shift from single object segmentation to detecting all matching object instances across an entire scene.

PCS looks like segmentation, but it has a detection-like failure mode: the model must decide whether the concept is present at all. That makes negatives and exhaustivity more central than in classic "segment the annotated objects" datasets.

That is the first big data implication:

- If your dataset is mostly positives, you can get good looking masks while still being unreliable as a tool.

- If your dataset does not check exhaustivity (missing instances), you can get good average quality while still failing in crowded scenes.

- If you don't train on difficult negative prompts, you can't calibrate presence confidently.

SAM 3's novel data engine is built around these issues.

2) Lineage: What SAM 3 Inherits from Earlier SAMs

SAM 3 is not starting from scratch.

- It inherits the basic "prompt → mask" framing from SAM 1 and improves previous SAM capabilities.

- It inherits video segmentation concepts (including mask propagation ideas) from SAM 2.

- It continues to rely on SA-1B, the large mask dataset created for the earlier SAM work, as part of its training mix.

This matters because it sets a baseline distribution of "what a segmentation mask looks like" and "what objects are common." If you train a model on SA-1B-like data, you bake in assumptions about:

- Photographic style and composition,

- Which objects appear often,

- How often objects are centered and well-lit,

- Which boundaries are ambiguous and how annotators tend to resolve that ambiguity.

SAM 3 tries to expand beyond that inherited distribution by introducing Segment Anything with Concepts (SA-Co): a dataset and benchmark designed to be explicitly open vocabulary and explicitly negative-heavy.

3) Training as Data Engineering: The Four Training Stages

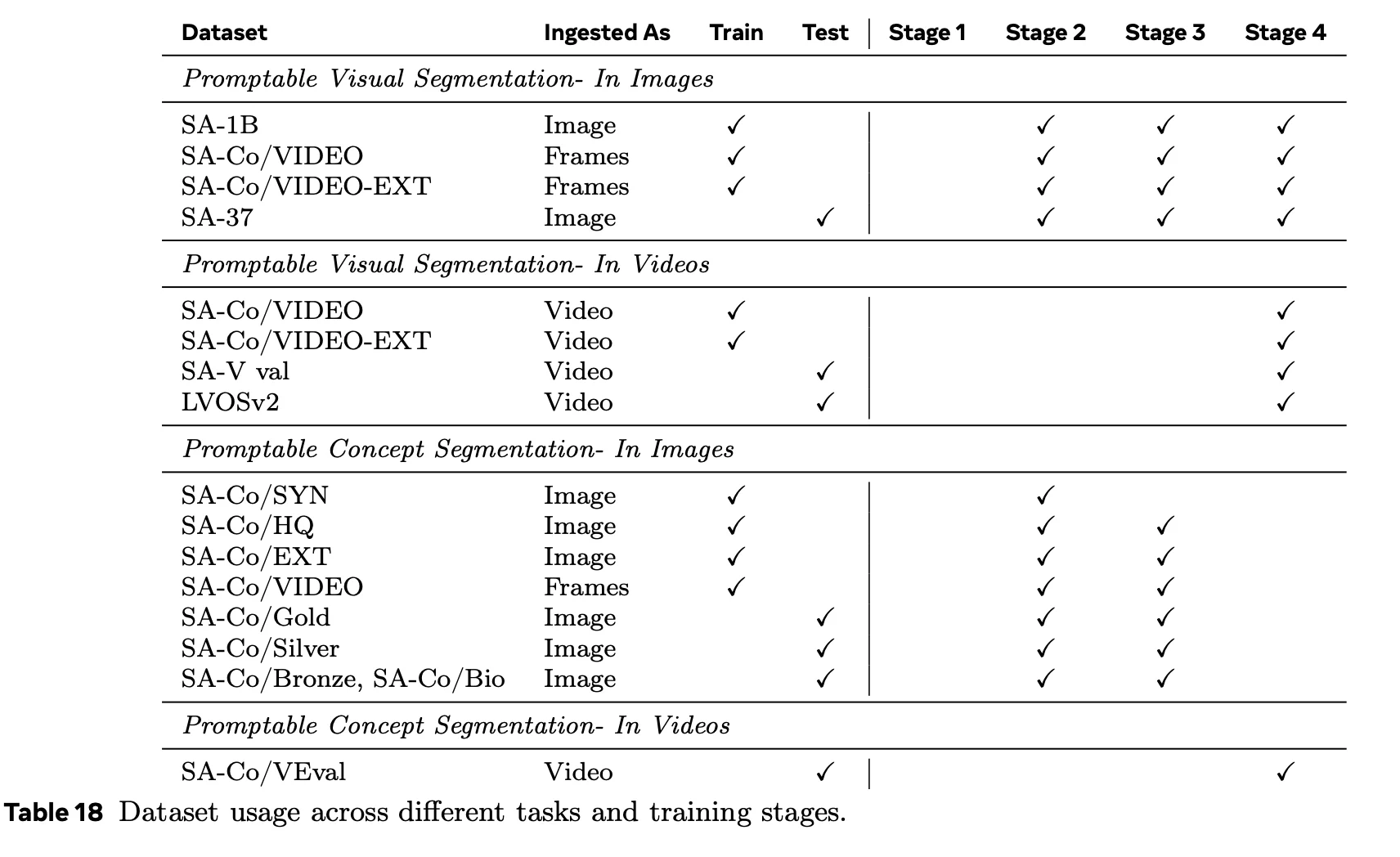

The paper describes four training stages, and each stage is essentially "add a new data source / distribution + train the system to use it."

Stage 1: Perception Encoder Pre-training (Image-Text)

The first stage pre-trains the image encoder and text encoders on billions of image-text pairs.

At a high level, this is where open vocabulary behavior begins: the model learns that text tokens correlate with visual patterns across many contexts. But this stage does not directly teach the model how to output masks. It teaches representations.

Data implication:

- If the image-text pairs have weak coverage in niche domains (medical imaging, underwater, microscopy), the encoder will be brittle there.

- If the text is noisy (alt-text that doesn't describe the image), you may get broad coverage but weaker grounding.

The paper emphasizes robustness as a key reason for this stage.

Stage 2: Detector Pre-training (Broad Concept Coverage)

Stage 2 adds large-scale segmentation supervision. This is where the model repeatedly sees tuples of:

- (input image, noun phrase, masks)

The stated goal is broad concept coverage across many domains, including data that is pseudo-labeled and data that is human-annotated.

A subtle but important data trick appears here: during training, some fraction of samples are transformed to better prepare the model for multiple prompt types:

- Sometimes the noun phrase is dropped (turning the problem into a visual query setting with image exemplar prompts),

- Sometimes an input box is added.

That is not an architecture change. It is a way of teaching the model a wider prompt distribution.

Stage 3: Detector Fine-tuning

Stage 3 is described as fine-tuning the detector. The details matter less than the intent: once Stage 2 gives broad coverage, Stage 3 leans harder on curated data to improve calibration, reduce systematic failure modes, and align the detector's outputs with how the memory based video tracker will use them later.

In practice, this kind of stage typically benefits most from:

- High-quality negatives,

- More consistent annotation protocols,

- Explicit coverage of difficult concepts (fine-grained and long-tail),

- And more domain diversity.

That is exactly what the SA-Co pipeline is designed to supply.

Stage 4: Tracker Training (Video, with a Frozen Backbone)

Stage 4 trains the tracker while keeping major parts of the backbone fixed. The training signal here is video-specific: the system must track objects and maintain identity and mask quality over time across video frames.

A tracker is only as good as its training clips. If clips are dominated by slow motion, clean objects, and few distractors, the tracker will look good and fail in the real world.

So the data question becomes: how do you systematically collect videos where tracking is genuinely hard but still annotatable?

The SAM 3 paper answers that with a video extension of the scalable data engine.

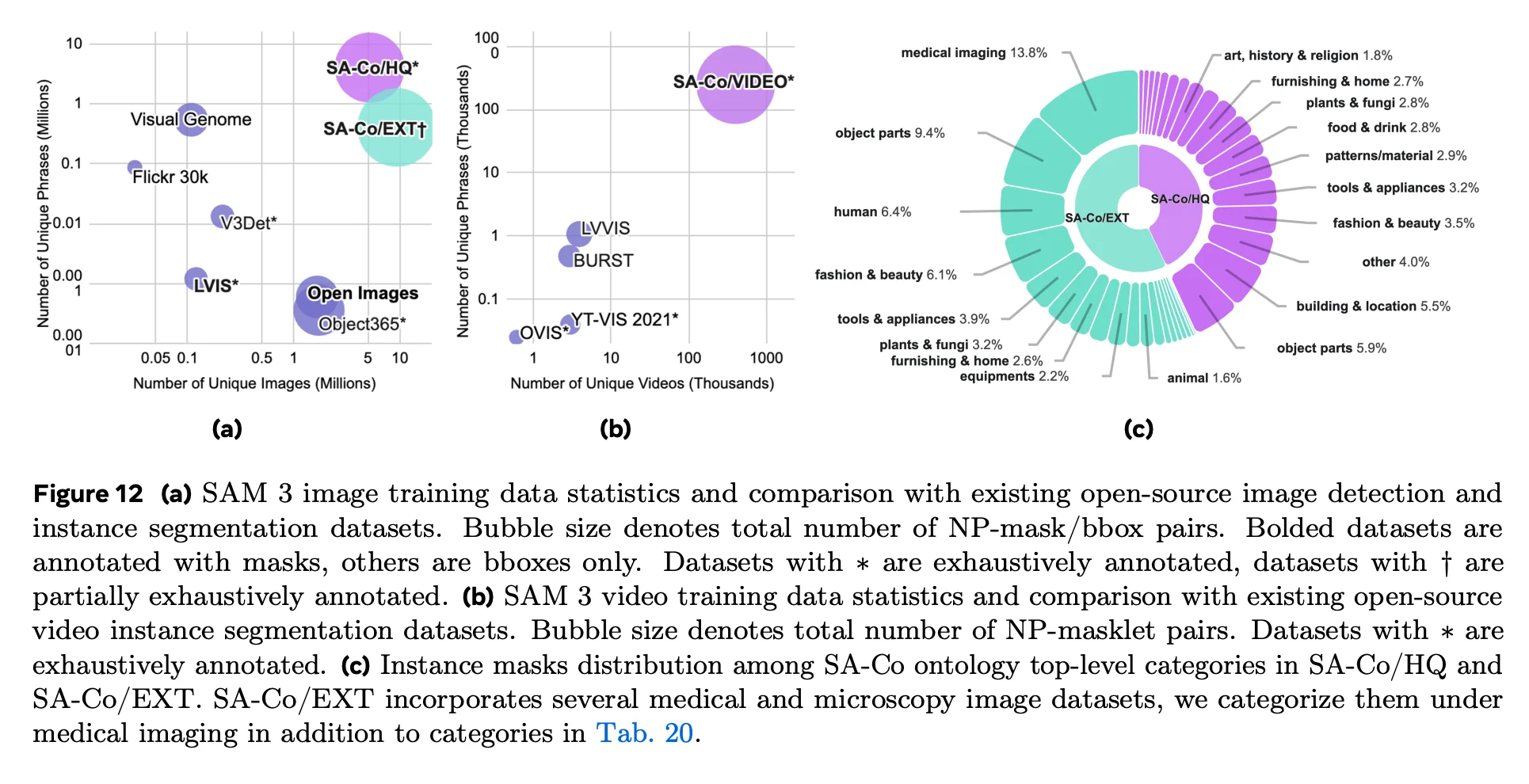

4) The SA-Co Training Sets: HQ, SYN, EXT, VIDEO

SA-Co is not "one dataset." It is a family of datasets built with different levels of human involvement and different sources.

SA-Co/HQ (High Quality)

This is the human-verified or human-corrected set collected through the data engine.

What makes it "HQ" is less about the source and more about the protocol: MV + EV verification, followed by human correction whenever EV fails.

A few concrete scale numbers help anchor what "HQ" means in this paper:

- 5.2M images with annotations.

- ~4M unique noun phrases (NPs).

- ~146M image–NP pairs, with a very high fraction labeled as negatives.

- ~52M instance masks associated with those pairs.

The heavy use of negatives is deliberate: promptable concept segmentation PCS is as much about deciding absence as it is about drawing masks.

More importantly, HQ is the dataset that the rest of the pipeline uses as a trusted reference when it wants to scale up automation.

The critical point is not just size. It's that HQ is created through a pipeline that explicitly checks:

- Mask quality (does the mask match the phrase?), and

- Exhaustivity (did you mask all instances of that phrase?),

and then sends failures to correction.

This reflects a fundamental truth that organizations building AI systems are increasingly recognizing: human expertise cannot be removed from the loop if you want reliable model performance. The data engine doesn't replace human judgment—it concentrates human effort where it matters most.

SA-Co/SYN (Synthetic at Scale)

This is a synthetic dataset produced by a mature version of the data engine without direct human involvement per sample.

What "synthetic" means here is not that images are generated. The images are mined (primarily from web-scale pools), and the labels—phrases, masks, negatives—are generated and verified automatically.

The key point is scale:

- ~39M images.

- ~1.7B image–NP pairs.

- ~1.4B masks.

This scale is not just "nice to have." It makes it feasible to cover long-tail visual concepts and to attach large numbers of hard negatives per image in a way that human annotation could not sustain.

The trade-off is that data quality is bounded by the verifier rubric and its blind spots, which is why the training mix still leans on HQ human-verified data as an anchor. Even with sophisticated AI verifiers, the system depends on human-generated ground truth to maintain calibration.

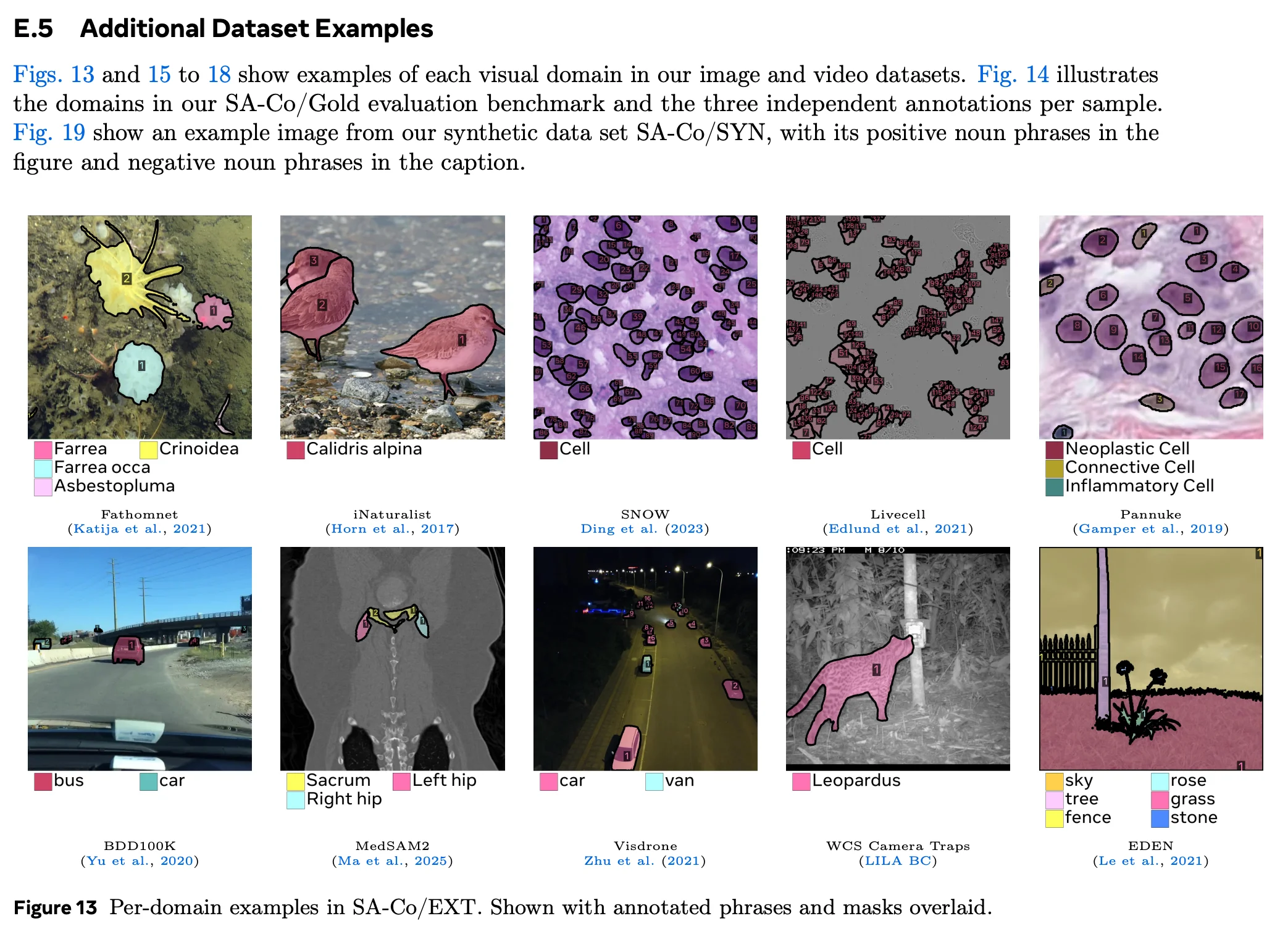

SA-Co/EXT (External Datasets, Unified and Enriched)

This subset pulls in multiple external datasets with masks or boxes.

In practice, it serves two purposes:

- Bring in domains that are hard to mine reliably from web pools (e.g., medical imaging, scientific, or structured settings).

- Provide a "known good" core of established annotations, even when the label space is closed-vocabulary.

Scale-wise, SA-Co/EXT is also large (millions of images and well over one hundred million image–NP pairs once mapped into the SA-Co label space).

Two data operations matter here:

- If a dataset has only bounding boxes, masks are generated using an existing model for object segmentation.

- Labels are mapped into a shared ontology, and additional negatives are proposed using the ontology hierarchy.

This turns "a pile of datasets" into a more coherent training distribution, and it makes the negatives story consistent across sources.

SA-Co/VIDEO (Human-Verified Video)

For video, the paper collects a dedicated dataset with masklets.

Here the paper is more conservative: video labels are human-verified, because tracking exhaustivity is expensive and errors are easy to miss.

A few concrete numbers:

- 52.5K videos.

- ~134K video–NP pairs.

- ~467K masklets.

- Videos average ~84 frames at ~6 fps (so the clips are short but non-trivial).

The key goal is not raw video count; it's collecting clips that stress:

- Occlusions,

- Fast motion,

- Multiple similar objects,

- Crowded scenes,

- And identity swaps.

That goal shows up in the mining filters and in how the pipeline filters out "easy" single-object clips. It is explicitly human-verified, because video exhaustivity is expensive and easy to get wrong.

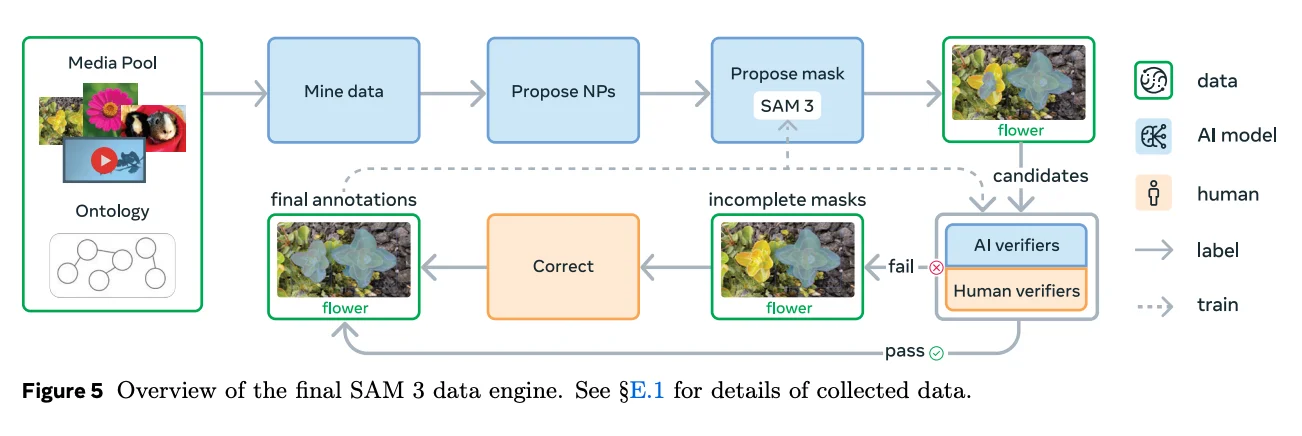

5) The Data Engine: Treat Annotation as a Feedback Loop

Like most of Meta's papers, the SAM3 one is explicit about the annotation pipeline. The novel data engine is a loop with three actors:

- SAM 3 (and existing models from earlier SAMs) producing candidate masks.

- Human annotators verifying and correcting.

- AI annotators / verifiers taking over high-volume, low-judgment steps once they match human performance.

The data engine allows for approximately 5x faster annotation on negative prompts and 36% faster on positive prompts compared to human-only pipelines—but this speed comes from augmenting human expertise, not replacing it.

The engine runs in four phases, each phase adding more automation and targeting harder cases.

The Core Components

The engine can be simplified into five steps:

- Mine media (images or videos) from large pools, guided by an ontology.

- Propose noun phrases (NPs) that describe visual concepts likely present.

- Propose masks for each NP.

- Verify masks in two steps:

- Mask Verification (MV): is the mask high quality and relevant to the phrase?

- Exhaustivity Verification (EV): are all instances covered? Are negatives correctly marked?

- Correct any media-phrase pairs that fail exhaustivity, by adding/removing/editing masks.

The repeated theme is that verification is not a side task. It defines the dataset.

6) Phase 1: Human Verification to Bootstrap Trust

Phase 1 starts simple:

- Sample images randomly from a web-scale pool,

- Generate captions and parse them into noun phrases,

- Use an open-vocabulary detector + SAM 2 to propose masks,

- Have humans do MV and EV.

The point of Phase 1 is not efficiency. It is to create a ground truth of accept/reject decisions so that later phases can train AI verifiers.

This is a common pattern in scalable data systems:

- Humans label the "judgment step" first.

- Models are trained to imitate that judgment.

- Humans shift to the tail of hard cases.

It is still human-in-the-loop. But the loop moves upward: humans define the rubric, the verifiers learn the rubric, then humans police the boundaries.

This pattern mirrors what enterprise AI teams discover when scaling annotation: you cannot fully automate quality without first establishing what quality means through expert human judgment. The most successful annotation platforms recognize that domain experts and subject matter specialists must remain central to the process, even as automation handles routine tasks.

7) Phase 2: Introduce AI Verifiers, Then Push Humans to the Hard Cases

Phase 2 is where the system becomes a data factory.

Instead of humans verifying every candidate mask and exhaustivity decision, the pipeline fine-tunes a multimodal large language model to act as AI verifiers for MV and EV.

What the AI Verifiers Actually Do

These verifiers take structured inputs like:

- The image,

- The phrase,

- The candidate mask (or its bounding box visualization),

and output a multiple-choice decision: accept, reject, whole-image, ungroundable, flagged label, etc.

This is not just "use an LLM." The verifier is trained on the specific verification distribution produced by Phase 1 humans. The rubric is explicit.

Why This Changes the Dataset

Once verification can run cheaply, the pipeline can:

- Collect many more candidate phrase–image pairs,

- Propose and verify many more negatives,

- And iterate the trained model more frequently.

But it also changes the failure modes:

- If the verifier becomes systematically biased (e.g., over-accepting masks in certain domains), the dataset can drift.

- If the verifier over-rejects small or ambiguous objects, the dataset can become too conservative.

This is why Phase 2 still keeps humans in the loop—just not everywhere.

8) The Ontology: The Hidden Steering Wheel of Data Collection

A large part of SA-Co's "coverage" comes from an explicit ontology built from Wikidata.

What the Ontology Is Used For

The ontology is not just a taxonomy for reporting statistics. It is used operationally for:

- Selecting concepts to mine,

- Balancing which concepts are over-represented,

- Mapping noun phrases into a canonical space,

- And generating hard negatives by traversing related nodes.

The paper describes an ontology with tens of millions of nodes, grouped into top-level categories and sub-categories. This enables SAM 3 to understand over 270,000 visual concepts without specific retraining for each object category.

Mapping Phrases into the Ontology

A practical challenge: "gray Siamese cat" and "Siamese cat" and "cat" are different phrases, and the pipeline needs to decide how to relate them.

The paper describes a mapping process that:

- Retrieves candidate Wikidata nodes using a text retrieval model,

- Then uses an AI judge to select the best match.

This mapping is foundational for both balancing and negative generation.

Data implication:

- If mapping is wrong, you might generate negatives that are not actually negatives.

- If mapping collapses too aggressively, you can lose fine-grained distinctions.

- If mapping is too literal, you can over-fragment the dataset and waste annotation effort.

This is a classic "taxonomy debt" problem: the more your pipeline depends on the ontology, the more you inherit its errors.

9) Mining Media: Avoiding "Whatever the Web Gives You"

Many open-vocabulary systems rely on uncurated web data. SAM 3 explicitly tries to avoid letting the web distribution dominate.

Media Pools and Domain Coverage

The paper uses a mixture of:

- Web-scraped image pools (with alt-text),

- Curated datasets for specific domains (e.g., driving, ego-centric videos, food, art, biology),

- And earlier SAM datasets like SA-1B.

The stated goal is to cover many distinct domains—where "domain" means a unique distribution of both text and visuals.

Why Domain Coverage Is Not Automatic

If you randomly sample web images, you tend to get:

- Product photos,

- Ads,

- Stock images,

- And over-represented everyday categories.

These images are not useless, but they can dominate the dataset and limit generalization.

The data engine introduces explicit mining and balancing steps (including image-type balancing) to avoid that collapse.

10) Proposing Noun Phrases: Where Quality Starts

Mask quality gets attention, but phrase quality is just as important in open vocabulary segmentation settings.

If your noun phrases include:

- Pronouns ("it", "them"),

- Vague spatial terms ("middle"),

- Or scene-level phrases ("a photo", "inside"),

then you create ambiguous supervision. Even worse, you create inconsistent supervision: different annotators will interpret these phrases differently.

Phrase Curation Is a Safety and Usability Issue

The paper's rubric includes a "flag label" option for phrases tied to sensitive attributes (race, ethnicity, religion, medical conditions, disabilities, derogatory terms, and similar categories). Even ignoring policy, this has a practical modeling point:

- These phrases are frequently ambiguous in imagery.

- They invite subjective or socially loaded interpretation.

- They are difficult to ground consistently.

Filtering them out is not only about ethics; it is also about preventing inconsistent supervision from corrupting calibration.

How SA-Co Improves Phrase Proposal

The pipeline evolves from early captioning + parsing into a stronger captioner and a fine-tuned phrase parser that proposes more diverse phrases.

Then it adds multiple filtering steps:

- Removing non-groundable phrases with a dedicated classifier,

- Singularizing and cleaning phrases,

- Deduplicating near-identical phrases,

- Removing possessives,

- And using balancing heuristics to avoid collecting only easy and frequent objects.

Balancing: Not Collecting What You Already Know

One under-appreciated part of dataset construction is when to stop collecting a concept.

The paper describes balancing heuristics like:

- Removing noun phrases if enough instances are already annotated,

- Removing phrases that the current model already handles with high accuracy,

- And removing phrases from fixed lists (including frequent or harmful ones).

This is active learning, but framed as data engineering rather than an algorithm.

11) Proposing Masks: Pseudo-Labels Are Not the Dataset

Mask proposal is initially done with a system like:

- An open-vocabulary detector proposes a box,

- SAM 2 turns the box into a mask.

As SAM 3 improves, SAM 3 itself becomes the proposer.

But mask proposal is not the dataset. Verification is.

Two operational details matter:

- Deduplication: masks for the same phrase are deduplicated using IoU.

- Trivial mask filtering: phrases that produce "the whole scene" masks are filtered.

There are also augmentation choices that show the authors are thinking about data consistency. One example described in the paper is mosaic augmentation (combining multiple images into a grid). In open vocabulary, mosaics are risky because the merged image may contain objects that were never annotated in one of the source images. The paper's approach is to apply mosaics only to sources where missing annotations are unlikely (closed vocabulary datasets, or sources mined in controlled ways), and then to merge labels using ontology mapping when possible.

These steps sound mundane, but they directly shape what the model learns:

- Dedup removes the incentive to over-segment duplicates.

- Whole-scene filtering prevents the model from learning that "background" answers are acceptable for certain prompts.

- Conservative mosaic usage avoids turning open-vocabulary uncertainty into systematic label noise.

12) Verification: MV and EV Define What "Good" Means

SA-Co uses two verification steps, and both are more structured than the typical "check the mask" flow.

A revealing detail is that verification is expressed as explicit categories rather than a continuous score. Examples include:

- Accept / reject decisions,

- Special handling for "whole image" phrases (scene descriptions that should not be segmented),

- An "ungroundable / vague / unsure" path (for phrases that don't have a stable visual referent),

- And a flag label path for sensitive or policy-relevant categories.

This matters because once you turn verification into categorical decisions, you can train a verifier model to reproduce the rubric consistently, and you can collect large volumes of "what not to train on" examples.

Mask Verification (MV)

This asks whether a given mask is:

- Accurate,

- Relevant to the phrase,

- And not a trivial or wrong region.

MV is mostly about precision.

Exhaustivity Verification (EV)

This asks whether:

- All instances of the phrase are annotated,

- Any missing objects exist,

- And whether a negative label is correct.

EV is mostly about recall and presence calibration.

Why EV Is Different but Important

In many segmentation datasets, exhaustivity is implicit: "these are the objects we labeled." In PCS, that is not enough.

If your dataset does not tell you "the phrase is not present," then your model can't learn reliable absence.

SA-Co solves this by explicitly collecting negatives and verifying them. A very large fraction of phrase–image pairs in the SA-Co evaluation benchmark are negatives.

This exhaustivity requirement is where human expertise becomes irreplaceable. AI verifiers can scale mask quality checks, but determining whether "all instances" have been captured—especially in complex, domain-specific imagery—requires the kind of contextual understanding that subject matter experts provide.

13) AI Verifiers: Scaling Supervision Without Losing the Rubric

Once MV and EV are labeled by humans in Phase 1, the pipeline trains AI verifiers to imitate the decisions.

Two points are worth emphasizing:

- The verifiers are not generic. They are trained on the exact rubric and failure modes of SA-Co.

- They are used both for synthetic data creation and for evaluation-time filtering / scoring.

What Counts as "Human-Level" Here

The paper compares human and AI verifier accuracy across multiple domains (web, SA-1B, attributes, crowded scenes, fine-grained food and sports equipment). The AI verifiers are described as matching or sometimes exceeding human performance on these tasks.

This is a good example of human experts concentrated at high leverage points:

- Humans define the verification categories.

- Humans produce the initial labeled verification data.

- AI verifiers scale that judgment.

- Humans remain for correction and for domain-specific gaps (especially exhaustivity in new domains).

Throughput Is Not a Side Benefit

Once verification becomes scalable, it unlocks:

- Large-scale hard negatives,

- Large-scale synthetic labels,

- And faster iteration cycles.

In other words: AI verifiers are a data scaling mechanism.

14) Correction: Where Humans Still Matter Most

Whenever EV fails, the pipeline enters manual correction.

Humans:

- Add missing masks,

- Remove incorrect masks,

- Edit boundaries,

- And sometimes use group masks for small, hard-to-separate objects.

Humans can also reject phrases as ambiguous or ungroundable.

This is where the dataset becomes high quality. Not because humans are slower, but because correction requires:

- Interpreting intent ("what does this phrase mean here?"),

- Resolving borderline cases,

- And making the dataset consistent.

The paper's pipeline uses automation to funnel human time into this correction step, rather than spending human time on easy accept/reject decisions.

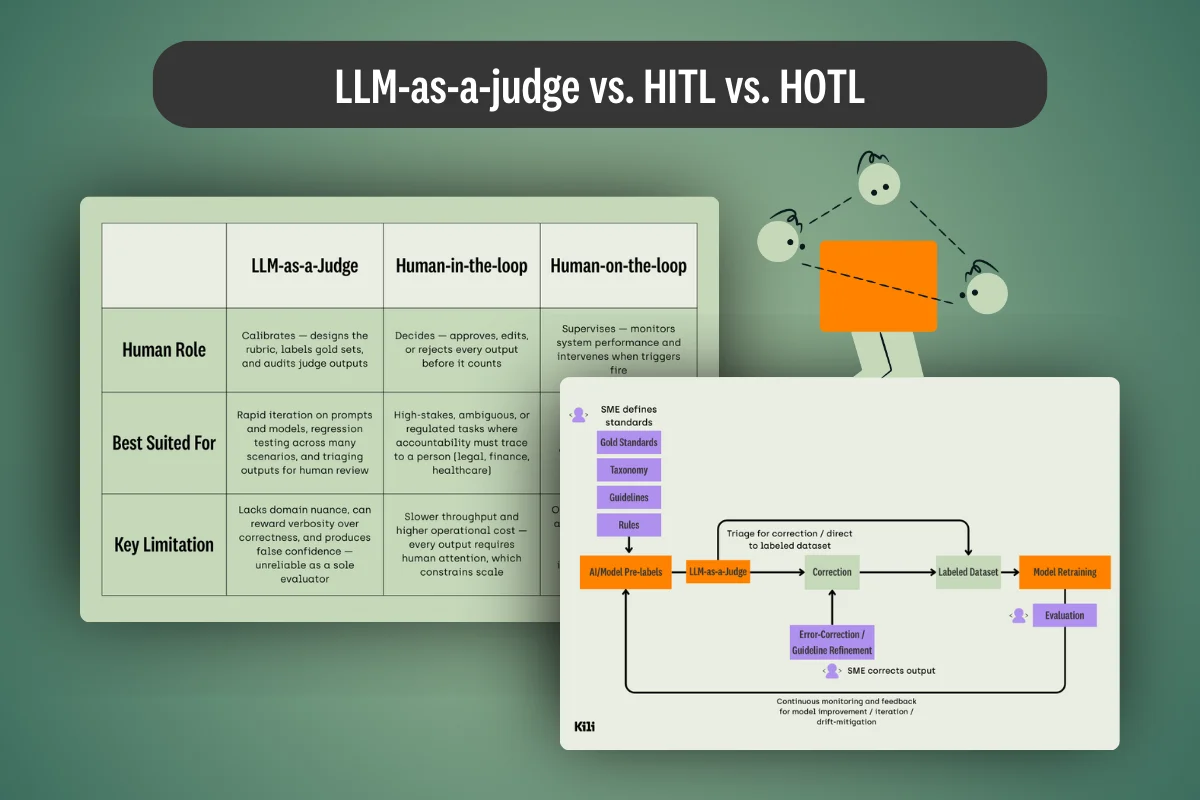

That is the core human-in-the-loop design. It recognizes a fundamental principle: while automation can handle volume, humans provide the judgment that determines whether a dataset actually teaches the right behaviors. This is especially critical when building models for interactive visual segmentation tasks, where errors compound in downstream applications.

15) Hard Negatives: Teaching Absence and Calibration

Hard negatives are a major theme in the SA-Co pipeline.

A "hard negative" is a phrase that:

- Does not exist in the image,

- But is similar enough to confuse the model.

Hard negatives matter because the image and video PCS metric rewards the model for:

- Saying "not present" when appropriate,

- And not hallucinating masks for related concepts.

How Hard Negatives Are Generated

The paper describes two main strategies:

- Ontology traversal: map a positive phrase to an ontology node, then generate siblings / cousins / uncles as negative candidates (e.g., "Siamese cat" → "tabby cat", "dog", "Chihuahua").

- MLLM generation: prompt a multimodal large language model to propose visually similar negatives.

Then a key filtering step is applied:

- Keep only negatives that are adversarial to the current SAM 3 version.

Concretely: if SAM 3 predicts an object for the negative phrase, the pipeline checks overlap with the positive masks. If the overlap is high enough, the negative is retained.

This matters because it prevents the dataset from filling up with easy negatives that teach nothing.

16) Phase 3: Scaling and Domain Expansion

Phase 3 expands in three directions at once:

- More domains (specialized datasets and media pools).

- More long-tail and fine-grained concepts (via ontology mining and alt-text).

- More challenging images (crowded scenes, small objects).

Crowdedness as a Mining Target

The paper describes mining crowded scenes using signals like:

- Object counts,

- Mask areas,

- And overlap statistics.

This is important because "crowdedness" is exactly where exhaustivity breaks down. If you do not mine for it, you will not fix it.

Domain-Specific Weakness: EV Does Not Transfer Perfectly

An interesting honesty in the paper: in new domains, MV works well zero-shot, but EV often needs modest domain-specific human supervision.

That makes sense: EV is about what counts as missing. In medical imaging, for example, what counts as a distinct instance can be fundamentally different from everyday scenes.

This is a concrete reminder that "AI annotators" are not a free lunch. They inherit domain assumptions from the training labels. Organizations building computer vision systems for specialized applications—whether in healthcare, manufacturing, or object and scene reconstruction—need domain experts involved in establishing what correct annotation looks like.

SA-Co/SYN: What You Gain, What You Risk

The synthetic dataset is built by:

- Mining images from large pools,

- Extracting noun phrases from alt-text and model-generated captions,

- Generating masks with SAM 3,

- Verifying with MV and EV AI verifiers,

- And generating and verifying hard negatives at scale.

The win is scale.

The risk is distributional bias:

- If the media pool has systematic skews, you amplify them.

- If the verifiers have blind spots, you scale the blind spots.

The paper's mitigation is to keep HQ human-verified data in the training mix and to use targeted mining rather than pure random sampling.

17) Phase 4: Extending the Engine to Video

Video adds two complications:

- Annotation cost explodes.

- Failure modes become temporal (identity swaps, drift, re-appearance).

So the video pipeline is designed to concentrate human effort on clips where temporal reasoning is genuinely required.

Masklets: How Labels Are Built

The pipeline:

- Proposes noun phrases,

- Uses a current SAM 3 to generate per-frame masks and then builds masklets,

- Deduplicates masklets,

- Filters out trivial cases (e.g., "whole scene" style outputs),

- And filters to keep multi-object scenarios (favoring crowded clips and multiple instances).

Early in the process, the system may rely on a separate propagation model; later it moves toward SAM 3 alone once video performance improves.

Human Verification and Correction Is Stricter in Video

Humans check:

- That the clip is usable (no cuts, split screen, explicit content),

- That the noun phrase is groundable across time (avoid comparison phrases and unstable attributes),

- And that the tracking is hard but still annotatable.

Then humans correct masklets:

- Remove incorrect ones (precision),

- Add missing ones (recall),

- And do a final exhaustivity pass.

The end product can be fully exhaustive or partially exhaustive (acknowledging that some instances may be impossible to separate).

That "partially exhaustive" label is a data design choice: it trades perfect completeness for realistic labeling constraints.

18) Fine-Tuning: The Paper's Clearest Lesson About Data Quality

The most useful part of the paper's fine-tuning discussion is that it makes the trade-offs visible.

Few-Shot Fine-Tuning for Detection

The paper evaluates few-shot fine-tuning on existing benchmarks with standardized splits.

Two details matter from a data perspective:

- In detection-only benchmarks (no masks), mask-specific losses are disabled.

- Hyperparameters are adapted (lower learning rate, small batch size, more epochs).

This is a reminder that "fine-tuning" is not one thing. The training objective changes with what labels are available.

SAM 3 excels at adapting to new domains with minimal user input and minimal examples—relevant for data-centric AI workflows—outperforming SAM 1 and SAM 2 in this aspect.

Domain Adaptation with Synthetic Labels

The paper includes a domain adaptation experiment in "Food & drink" concepts that isolates how different label qualities scale:

- Pseudo-labels without cleaning,

- Synthetic labels cleaned by AI verifiers,

- Human-verified high quality labels.

A key result is that synthetic data cleaned by AI verifiers can approach the scaling behavior of human-verified data, and can eventually catch up—especially when mixed with high-quality pre-training data.

The mixing point matters. When you fine-tune only on new domain synthetic data without mixing strong pre-training data, gains can be limited.

This is a practical rule:

- If your new domain labels are weaker (even if large), mixing with strong general data can stabilize learning.

- If you drop the strong general data, the model may overfit noise or collapse calibration.

19) Evaluation Is Also a Dataset: SA-Co Benchmarks and What They Test

Before getting into metrics, it helps to treat the benchmark itself as a curated distribution. SA-Co evaluation is intentionally built to include:

- Many domains (not just "internet photos"),

- Heavy negative labeling,

- And explicit measurements of ambiguity.

At a headline level, the SA-Co evaluation benchmark contains 214,000 unique phrases across 126,000 images and videos, providing over 50 times more concepts than existing benchmarks. This includes millions of media–phrase pairs with hard negatives.

The split structure is then a way to make measurement trade-offs explicit.

Why Multiple Splits Exist

Each split represents a different quality / cost trade-off, and the paper gives enough statistics to see what the authors are optimizing for.

- Gold: On the order of tens of thousands of unique phrases and tens of thousands of images; each image–phrase pair is annotated by three different annotators.

- Silver: Similar phrase scale but much larger image scale; typically one annotation per pair.

- Bronze/Bio: Existing datasets (some with masks generated from boxes), used to test transfer and domain shift.

- VEval: A dedicated video benchmark with a smaller but carefully curated set of video–phrase pairs.

This structure is a data-centric approach to evaluation:

- Gold gives you clean measurement and a way to estimate human performance.

- Silver gives you scale and diversity.

- Bronze/Bio give you transfer checks.

- VEval gives you temporal stress tests.

In a sense, the benchmark is designed the same way as the training data: split by cost and certainty.

Hard Negatives Are Central in Evaluation

The evaluation sets include many hard negatives. That matters because it makes the benchmark sensitive to "hallucinated presence," not just mask quality.

Many existing benchmarks fail to test absence robustly.

Domains Matter More Than Dataset Names

The paper describes evaluation domains spanning:

- Web pools,

- SA-1B,

- Attributes,

- Crowded scenes,

- Fine-grained ontology concepts,

- Driving and ego-centric footage,

- And biology / medical imagery.

This domain approach is important because "generalization" is really "did you train on something similar?" A domain list makes those similarities explicit.

20) Metrics: Why SAM 3 Emphasizes Calibration

The paper introduces metrics designed to reflect tool usefulness rather than "best possible mask if you tune a threshold."

Classification-Gated F1 (cgF1)

cgF1 combines two things:

- A localization score on positives, and

- A classification score for presence/absence.

This design forces the model to be both:

- Good at drawing masks when present, and

- Good at saying "not present" when absent.

Thresholding as an Evaluation Choice

The paper evaluates predictions above a fixed confidence threshold to mimic downstream usage.

This is an explicit stance:

- A model that only works if you tune thresholds per dataset is not very usable as a general tool.

- Calibration is part of performance.

That stance matches the data engine's focus on hard negatives and exhaustivity.

Ambiguity: Measuring the Ceiling

For Gold, multiple human annotations per pair allow an "oracle" style evaluation where ambiguity is acknowledged.

This matters because some phrases are inherently ambiguous. If your dataset pretends ambiguity doesn't exist, it can punish models for reasonable interpretations.

The paper's approach makes that ambiguity visible.

21) A Revealing Detail: AI Verifiers Can Improve Evaluation Performance

One of the more interesting results is that adding AI verifiers on top of SAM 3 can improve measured performance.

How?

- The EV verifier provides a presence score that can be better calibrated than the model's own scores.

- The MV verifier can filter out low-quality masks.

In other words, a better judge can make the system more usable even if the underlying mask generator is unchanged.

This reframes part of the problem:

- Some "model performance" is actually "how well you can score, filter, and calibrate outputs."

And that is again a data story: the judge is trained on human verification data.

22) How the Data Choices Show Up in Performance

SAM 3 achieves a 2× performance gain over existing systems in promptable concept segmentation while maintaining and improving previous SAM capabilities for interactive visual segmentation tasks.

The model runs in approximately 30 milliseconds for a single image with more than 100 detected objects—an improvement over previous models that enables real-time applications in creative media tools, fun video edits, magnifying specific objects, and scientific research.

At a high level, the paper reports strong results across:

- Open vocabulary concept segmentation,

- Box detection,

- Semantic segmentation,

- Video segmentation and tracking,

- And object counting.

Rather than repeating scores, it is more useful to connect the performance patterns to data choices.

(a) Broad Concept Coverage Is Mostly a Mining and Phrase Problem

When models fail "open vocabulary," it is often not because the mask head can't draw boundaries. It is because:

- The phrase was not seen often enough,

- The phrase was seen only in narrow contexts,

- Or the dataset never forced a reliable absence decision.

SA-Co addresses this with:

- Ontology-guided concept selection,

- Explicit long-tail mining,

- And heavy negative annotation.

(b) Crowded Scenes Are Mostly an Exhaustivity Problem

Crowded scenes stress:

- Recall,

- Instance separation,

- And "how many objects should exist."

SA-Co targets crowdedness explicitly, both in mining and in verification. That should directly impact performance in multi-object settings.

(c) Fine-Grained Concepts Require Both Good Phrase Normalization and Good Negatives

If you want "kefir" to be different from "yogurt," you need:

- Consistent phrase mapping,

- Concept selection that ensures coverage,

- And negatives that teach the boundary.

Ontology traversal + adversarial filtering is designed for exactly that.

(d) Video Performance Depends on Clip Selection More Than Algorithm Tweaks

Tracker improvements are often attributed to clever re-prompting rules or association modules.

But without video training clips that contain:

- Many similar objects,

- Occlusions,

- Fast motion,

you can't learn a robust tracker.

The video data engine is essentially a clip selection and labeling strategy designed to create those situations.

SAM 3 shows significant improvements over SAM 2 and prior state-of-the-art across video benchmarks such as DAVIS 2017 and YouTube-VOS. It produces sharper edges, precise contours, and better separation between touching objects compared to SAM 1 and SAM 2.

23) Human Experts in the Loop: Where They Actually Sit

It's tempting to summarize SAM 3 as "automated annotation." That misses where the human leverage is.

Humans show up in at least five high-impact places:

- Defining the verification rubrics (MV and EV categories).

- Creating the initial verifier training data (Phase 1).

- Manual correction of non-exhaustive cases (where judgment is required).

- Domain adaptation for EV (where "missing instance" semantics change).

- Video ground truth refinement (multiple rounds to guarantee quality).

In other words: humans are not removed. They are repositioned.

The pipeline tries to automate the repeatable parts (verification at scale) while reserving humans for:

- Ambiguity,

- Edge cases,

- And shifts in domain semantics.

This is the core pattern you see in many successful modern training systems. The most effective data annotation platforms recognize that automation serves to multiply human expertise, not replace it. When enterprises need to build production-ready AI systems—whether for promptable visual segmentation, image recognition, shape estimation, or other visual segmentation tasks—the critical question is not "how do we remove humans?" but "how do we position human expertise where it creates the most value?"

24) Limitations and Transparency Gaps

Even with a detailed data engine description, some practical uncertainties remain.

Perception Encoder Pre-training Data Is Not Fully Inspectable

The paper describes billions of image-text pairs, but the exact composition and filtering of that corpus is not fully open.

That constrains external reasoning about:

- Domain coverage,

- Demographic representation,

- And potential bias inherited before SA-Co ever enters the picture.

Synthetic Scaling Amplifies Verifier Assumptions

If MV/EV verifiers have blind spots, SA-Co/SYN can scale those blind spots. This is not an accusation; it's a standard property of automated labeling.

The mitigations appear to be:

- Mixing HQ human-verified data,

- Targeted mining,

- And continued human correction.

But external users should still expect that synthetic data will be "high quality" in the sense of the verifier rubric—not necessarily in the sense of every downstream domain.

Ontology Mapping Can Be a Quiet Source of Error

The more the pipeline uses ontology mapping (balancing, negatives, domain tracking), the more sensitive it is to mapping errors.

That is not a reason to avoid ontologies. It is a reason to treat mapping as a core system component that needs evaluation, monitoring, and periodic human review.

Closing Synthesis

SAM 3 is often framed as a model upgrade. A more accurate summary is that it is a data system that happens to output a model.

The paper's strongest idea is the feedback loop:

- Mine what the model fails on,

- Propose labels,

- Verify and correct with a rubric,

- And scale verification with AI once humans have anchored what "good" means.

To understand why SAM 3 improves, it all lies within the data.

Start with the dataset decisions that make "absence," "exhaustivity," and "hard negatives" unavoidable.

Those decisions are what reshape the model's experience—and ultimately, its behavior in the open world.

The meta-lesson for any organization building visual AI systems is clear: model architecture matters, but data quality determines whether your system works in production. The most sophisticated model trained on inconsistent, incomplete, or poorly verified data will underperform a simpler model trained on data that has been validated by domain experts who understand what "correct" actually means in context.

SAM 3's success is not primarily an architecture story. It is a demonstration of what becomes possible when you treat human expertise as a force multiplier rather than a bottleneck—when you build systems that concentrate expert judgment where it matters most while using automation to handle scale.

That principle applies whether you're building promptable visual segmentation models, referring expression segmentation systems, or any application where computer vision meets the complexity of the real world.

Other Data Stories:

Data Story: How the Corpus, Synthetic Pipelines, and Evaluation Shaped Deepseek V3.2

Qwen 3: A Deep Dive into Its Data Pipeline

FineWeb2 Dataset Guide: How It's Built, Filtered, and Used for Training LLMs

.png)

_logo%201.svg)

.webp)